The picture of a thousand choices

A project for Spanish class turns into a journey not just towards one's roots, but towards the choices that turned them into the person they are today.

“Your existence is proof that generations of your face have been loved.”

—Unknown

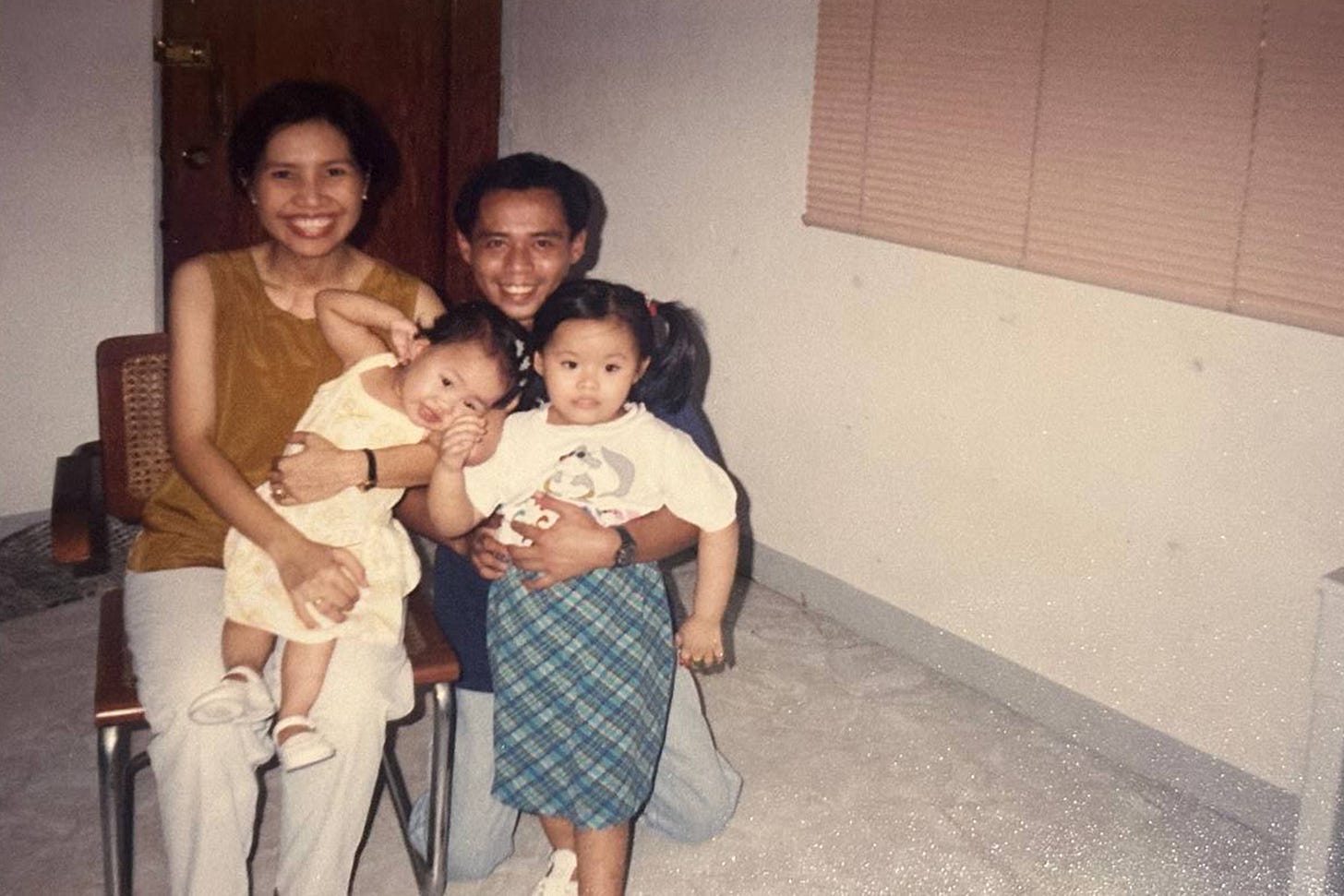

As a kid, I often wondered why I didn’t look like anyone in my family. I didn’t have Mommy’s fair skin, nor did I have Daddy’s curly hair. Nor did I look like any of my grandparents, aunts, or uncles. My younger sister, who was fair like Mommy but resembled Daddy’s mother, was deemed the “conventionally pretty” one. Meanwhile, I, with my morena complexion, glasses, and plain Jane features, was asked point-blank by a classmate: “Why don’t you look like your sister?”

In family pictures and graduation photos, I struggled to find a common link between myself and the two people I was supposed to look like.

I would even ask Mommy if she was sure I wasn’t swapped at birth like those telenovela babies. No, she would assure me. Her sister, my aunt, was a doctor in the same hospital where I was born, and they were 100% sure I was Mommy’s and Daddy’s.

Back in my third year of high school, we had to choose an elective. As someone who had long been interested in history and Europe, I chose to take Spanish. One of our assignments was to create our family tree, up to our great-grandparents. This would help us learn the Spanish words for family members beyond padre (father), madre (mother), and hermana (sister).

Naturally, I asked my parents for some help with the assignment.

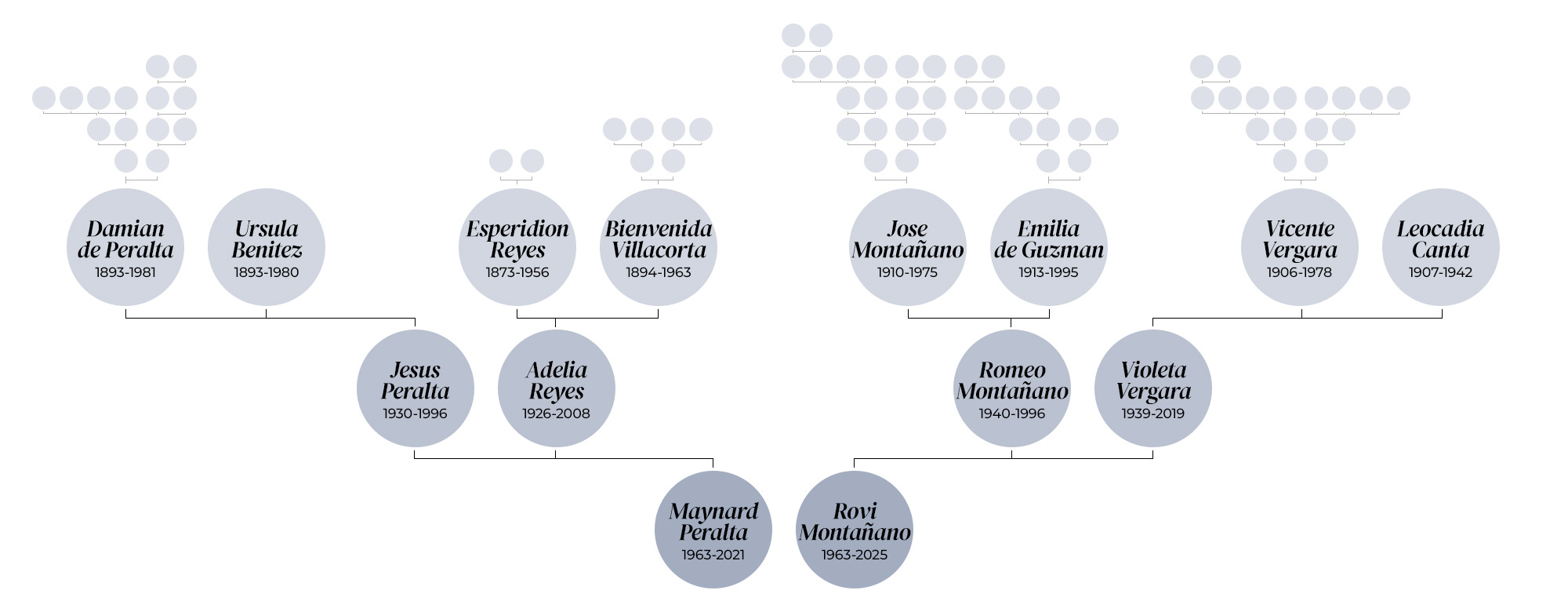

First, there were Mommy’s paternal grandparents. There was Lolo Jose “Jo” Montañano, who hailed from Nagcarlan, Laguna. He married Lola Emilia “Mening” de Guzman from Alaminos, Pangasinan. They settled in Alaminos where they had my grandfather, Romeo Montañano. He grew up to be “Papa” to my mother and her siblings, before passing away in 1996, before I could remember him.

On the other side, her maternal grandparents were Lolo Vicente “Enteng” Vergara, from San Isidro, Nueva Ecija; and Lola Leocadia Canta, from Santo Tomas, Batangas. She died when her only daughter, Violeta, was very young.

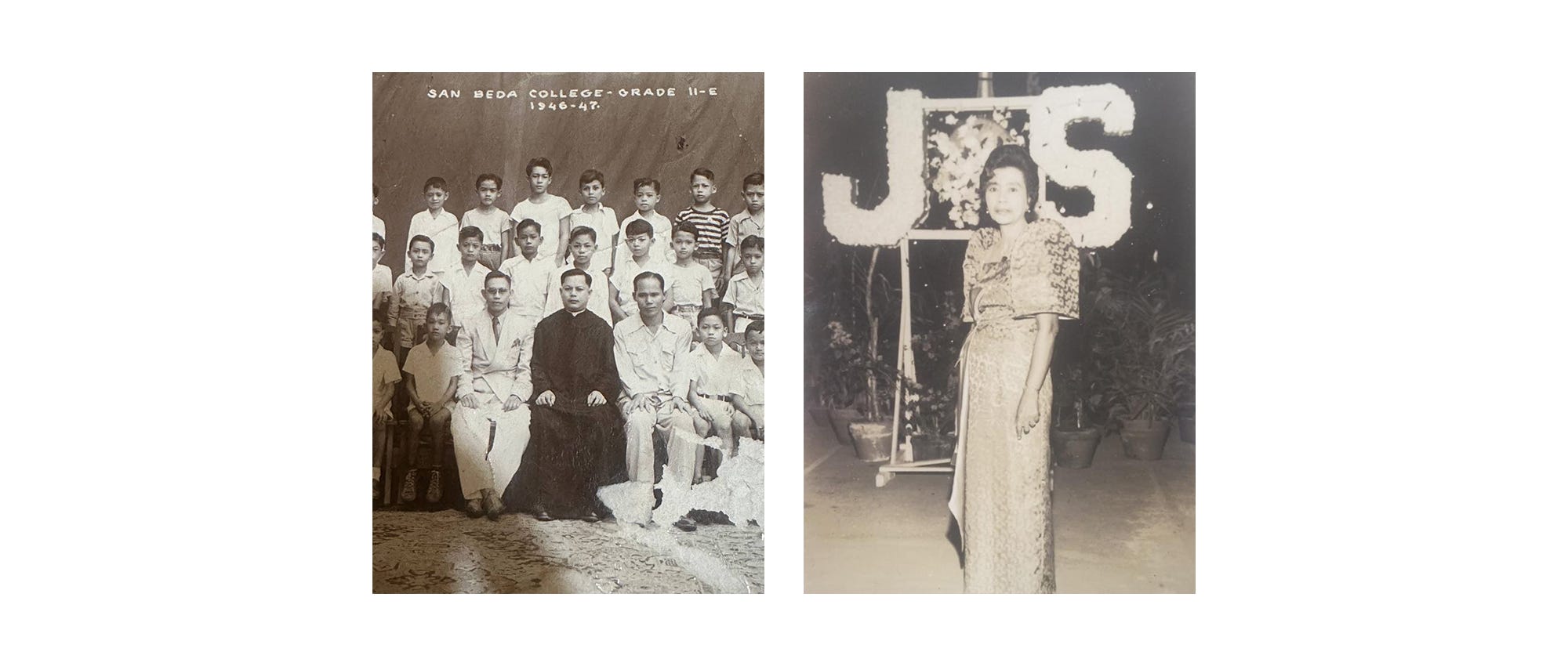

Daddy’s paternal grandparents were Damian G. de Peralta and Ursula Benitez. They had my Lolo, Jesus “Jesse” Peralta, who also passed in 1996. According to Daddy, they had roots in Santa, Ilocos Sur.

On his mother’s side were Bienvenido Reyes and Bienvenida Villacorta, the parents of Lola Adelia “Dely” Reyes. Funny coincidence with the names, I know—but this would later turn out to be an error, as “Bienvenido” was actually “Esperidion”.

As far as we knew, Lola’s roots were in San Jose, Nueva Ecija, though I had heard some mentions of other hometowns like Muñoz, Nueva Ecija, and a town in Bulacan. Unfortunately, Lola and I were never close, and she passed away on my first day of high school, so I never got to know more.

Fascinated by this new knowledge about my roots, I went on my merry way to memorize words like bisabuelos (great-grandparents), primo (male cousin), and sobrina (niece).

It wasn’t until after college that I got curious about my family tree again.

Mommy’s side of the family had recently made it a tradition to have a trip between the Christmas and New Year holidays. Leaving Mama and our pets to the “care” of Daddy, we booked trips to Alaminos, where we saw the beautiful Hundred Islands, ate the town’s famed longganisa, and tried to look for vestiges of the de Guzman clan in the nearby cemetery and town. But, with most of the family off in America, there was no one left to visit the graves. And since the ancestral house had been sold off to fund tuition fees for Mommy and her siblings, there was really no “home” to come home to.

One afternoon, on All Saints’ Day, I decided to visit Mama—Mommy’s mother, Violeta—and ask her about our family tree. I was always closer to Mommy’s side of the family, and I felt right at home asking about names, occupations, and even meet-cutes. In just one afternoon, I had a whole list of distant relatives… plus a healthy dose of family secrets.

That same year, we went to Nagcarlan. We visited the famed underground cemetery and found Montañanos, as well as Consignados and Coronados—distant relatives, Mommy said. We also ended up doing a “door-to-door” in the town and asking around if anyone remembered Jose Consignado Montañano who moved to Pangasinan in the 1940s. We found some distant relatives that way, too!

It was lucky that I had asked Mama all those questions when I did. In 2019, she was diagnosed with cancer and passed away less than six months later. The following year brought the pandemic and my parents’ cancer diagnoses.

Sadly, we never got the chance to travel with Mama to one of her hometowns.

Fast forward to mid-2024. My mother, still ill with cancer, had recently retired, and was spending her time consulting her many doctors, ordering her various medications, and keeping up her correspondence with family members and friends. Out of curiosity, I started documenting our family tree on Family Search. I’d work on it during lunch breaks and after work, asking Mommy questions about Mama’s cousins, what she knew about Daddy’s aunts and uncles, and asking her to message those distant relatives in America.

My family tree project soon became a bit of a hobby. I was always trying to go back one more generation. Learn one more date. See one more birth or marriage certificate. Find one more lead. I did find dozens of Peraltas, Montañanos, de Guzmans, and Vergaras, and a handful of Cantas, Reyeses, and Villacortas, too. The Benitezes remain a dead end, though.

It soon became an obsession. Maybe the more I knew about my roots, the longer Mommy would stay. We could talk about the various relatives on her side. We could plan visits to Santo Tomas and San Isidro—places she herself hasn’t seen.

Maybe, if I kept her engaged and interested in the past, and excited about my future wedding, she would be healed and stay on as another generation began.

As of writing, I’ve traced my roots back to the 1800s, for most of my great-grandparents.

And what have I learned from this months-long, still ongoing project?

More than names, dates, and places, more than jobs or the average number of kids a family would have, more than the shocking ages of brides and grooms or the infant mortality rate… I realized that my being here is the result of so many choices, made by so many people.

What if Lolo Martin Montañano had chosen to settle in another town? What if he hadn’t stayed in Nagcarlan, like his entire family did, and he hadn’t met Lola Maria Ortega and had ten kids with her?

What if Lola Agata Galinato’s parents had stopped at eight kids, and she was never born, meaning she would never have my great-grandfather, Damian?

What if Lolo Esperidion Reyes hadn’t left San Miguel, Bulacan? What if he hadn’t remarried, and had my Lola Dely when he was well into his fifties?

What if Lola Leocadia Canta had chosen to take a trip and missed whoever it was that caused her tuberculosis? Would her daughter, my Mama Violy, have grown up differently, and ended up with another man who wasn’t Papa Romy?

What if Lolo Jesse and Lola Dely had been able to support Daddy at law school full-time? Would he have decided not to work? Would Mommy have ended up with someone else? Oh, she might have been spared so much pain.

What if all those had happened? Of course, I wouldn’t exist.

Because of the choices they made, I exist.

So many choices, it’s practically a coincidence that I’m here at all.

But it wasn’t my choice to be here. In the same way that it’s no one’s choice to be here. We had no say in the moment of our conception, or the circumstances of our birth.

It’s a bold thing to claim, too, that any of my ancestors had a lot of choices—or any more than we do today.

Who knows what they were up against, back in the days of Spanish colonization? Even the Dons and Doñas in my family tree may have been caught between complacent comfort and risky rebellion. And all those children—was it ever the woman’s choice to have more, year after year? Who knows.

Because of their choices, my parents got their lot in life—the opportunities they enjoyed, and the chances they missed out on.

And yes, they made their own choices. To take up this course in university, to apply to this job. To get together. To stay together. To stop post-grad and settle down. To put me through private school. To subject me to the trauma of their fights. To stay put in the Philippines instead of migrating. To stay together instead of separating.

And I can have my own feelings now about those choices. I can question them as much as I like. But it’s all moot now, right?

Because of their choices, I sit here breathing, writing. In front of a computer I bought with my own money. Money from a job I chose to apply for. A job I qualified for because of a course I chose. And I was only able to get into that course, or even reach college, because of choices made for me. And choices made by those who came long before me.

Because of their choices, I have this life.

Because of their choices, I have this face. Features that have been chosen by husbands in their wives, by young girls in their choice of suitor.

Funnily enough, I can finally see bits of my parents and grandparents reflected in my face, and in my personality. What resemblance I couldn’t discern at age 9, I now find at 30.

And while I had no say in this existence, I can choose to make the most of it. I can choose to embrace what I’ve loved and appreciated in my parents and grandparents, and what they’ve told me of their own ancestors. I can also choose to take a different path—choose my mental health through therapy, choose a man who truly loves me.

They’ve made their choices. Now, it’s time to make mine.

The title of this essay is inspired by the song “Paint My Love” by Michael Learns to Rock, a Danish band that was quite popular in the Philippines back in the ‘90s.

The author’s mother, Rovi, passed away before the publication of this essay.

About the author—

is an advertising copywriter based in Manila. She likes to garden, listen to old music, read, drink tea and eat sweets. A furmom to Auro (and fur-aunt to another, Hershey), she is also a zero-waste advocate. She is the writer behind and .

Beautifully written. 🤍

My deepest condolences, Regina. 💐

Genealogist Mona Magno-Veluz has been open about using Mormon resources for her work. https://www.facebook.com/mightymagulang/posts/i-am-not-a-member-but-the-church-helped-me-when-i-started-with-genealogy-more-th/163395539610178/ Baka you'll uncover more info if you go to the facility mismo. Been thinking about looking into my tree this way along with Family Search ☺️

Also, my condolences to you and your sister 💗